Chinese sages said that if a person has a healthy intestine, he can overcome any disease. Delving into the work of this organ, you never cease to be amazed at how complex it is, how many degrees of protection are built into it. And how easy it is, knowing the basic principles of its work, to help the intestines maintain our health. I hope that this article, written on the basis of the latest medical research by Russian and foreign scientists, will help you understand how the small intestine works and what functions it performs.

Content

Structure of the small intestine

The intestine is the longest organ of the digestive system and consists of two sections. The small intestine, or small intestine, forms a large number of loops and continues into the large intestine. The human small intestine is approximately 2.6 meters long and is a long, tapering tube. Its diameter decreases from 3-4 cm at the beginning to 2-2.5 cm at the end.

At the junction of the small and large intestines there is an ileocecal valve with a muscular sphincter. It closes the exit from the small intestine and prevents the contents of the large intestine from entering the small intestine. From 4-5 kg of food gruel passing through the small intestine, 200 grams of feces are formed.

The anatomy of the small intestine has a number of features in accordance with its functions.

So the inner surface consists of many semicircular folds . Thanks to this, its suction surface increases 3 times.

In the upper part of the small intestine, the folds are higher and located closely to each other; as they move away from the stomach, their height decreases.

They may be completely absent in the area of transition to the large intestine.

Sections of the small intestine

The small intestine has 3 sections:

- duodenum

- jejunum

- ileum.

The initial section of the small intestine is the duodenum.

It distinguishes between the upper, descending, horizontal and ascending parts. The small intestine and ileum do not have a clear boundary between themselves.

The beginning and end of the small intestine are attached to the posterior wall of the abdominal cavity.

Throughout the rest of its length it is fixed by the mesentery. The mesentery of the small intestine is the part of the peritoneum that contains blood and lymphatic vessels and nerves and allows intestinal motility.

Blood supply

The abdominal part of the aorta is divided into 3 branches, two mesenteric arteries and the celiac trunk, through which blood is supplied to the gastrointestinal tract and abdominal organs. The ends of the mesenteric arteries narrow as they move away from the mesenteric edge of the intestine. Therefore, the blood supply to the free edge of the small intestine is much worse than the mesenteric one.

The venous capillaries of the intestinal villi unite into venules, then into small veins and into the superior and inferior mesenteric veins, which enter the portal vein. Venous blood first flows through the portal vein into the liver and only then into the inferior vena cava.

Lymphatic vessels

The lymphatic vessels of the small intestine begin in the villi of the mucous membrane; upon leaving the wall of the small intestine they enter the mesentery. In the mesenteric area, they form transport vessels that are capable of contracting and pumping lymph. The vessels contain a white liquid similar to milk. That's why they are called milky. At the root of the mesentery are the central lymph nodes.

Some lymphatic vessels may empty into the thoracic stream, bypassing the lymph nodes. This explains the possibility of rapid spread of toxins and microbes through the lymphatic route.

Mucous membrane

The mucous membrane of the small intestine is lined with single-layer prismatic epithelium.

Epithelial renewal occurs in different parts of the small intestine within 3-6 days.

The cavity of the small intestine is lined with villi and microvilli. Microvilli form the so-called brush border, which provides the protective function of the small intestine. Like a sieve, it sifts out high-molecular toxic substances and does not allow them to penetrate the blood supply and lymphatic system.

Nutrients are absorbed through the epithelium of the small intestine. Through the blood capillaries located in the centers of the villi, water, carbohydrates and amino acids are absorbed. Fats are absorbed by lymphatic capillaries.

The formation of mucus lining the intestinal cavity also occurs in the small intestine. It has been proven that mucus performs a protective function and helps regulate intestinal microflora.

Functions

The small intestine performs the most important functions for the body, such as

- digestion

- immune function

- endocrine function

- barrier function.

Digestion

It is in the small intestine that the processes of food digestion occur most intensively. In humans, the digestion process practically ends in the small intestine. In response to mechanical and chemical irritations, the intestinal glands secrete up to 2.5 liters of intestinal juice per day. Intestinal juice is secreted only in those parts of the intestine in which the food lump is located. It contains 22 digestive enzymes. The environment in the small intestine is close to neutral.

Fright, angry emotions, fear and severe pain can slow down the functioning of the digestive glands.

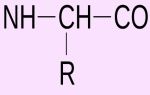

Food contains proteins , fats, carbohydrates and nucleic acids. For each component, there is a set of enzymes that can break down complex molecules into components that can be absorbed.

Absorption in the small intestine occurs throughout its entire length as food masses move through. Calcium, magnesium, and iron are absorbed in the duodenum; mainly glucose, thiamine, riboflabin, pyridoxine, folic acid, and vitamin C are absorbed in the jejunum. Fats and proteins are also absorbed in the jejunum.

Vitamin B12 and bile salts are absorbed into the ileal cavity. The absorption of amino acids is completed in the initial parts of the jejunum. Digestion in the human small intestine is the most important and at the same time the most complex function.

The immune system

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of the immune function of the intestines for maintaining the health of the body. It provides protection against food antigens, viruses, bacteria, toxins and drugs.

The mucous membrane of the small intestine contains more than 400 thousand per square meter. mm of plasma cells and about 1 million per square meter. see lymphocytes. This means that in addition to the epithelial layer that separates the external and internal environment of the body, there is also a powerful leukocyte layer.

Cells of the small intestine produce a number of immunoglobulins, which are absorbed on the mucous membrane and provide additional protection, forming the body's immunity.

Endocrine system

The small intestine is an important endocrine organ.

The number of endocrine cells in the small intestine is no less in mass than in such endocrine organs as the thyroid gland or adrenal glands.

More than 20 hormones and biologically active substances that control the functions of the gastrointestinal tract have been studied. In addition, it is known how they act in the body. The network of neurons located in the intestinal wall regulates intestinal functions with the help of various neurotransmitters, and is called the intestinal hormonal system.

Protective function

The process of breakdown of nutrients includes not only the supply of plastic and energy materials, but there is a danger of toxic substances entering the internal environment of the body. Foreign proteins pose a particular danger. During the process of evolution, a powerful protective system has formed in the gastrointestinal tract.

The effectiveness of the barrier function of the small intestine depends on its enzymatic activity, immune properties, the presence and condition of mucus, structural integrity, and degree of permeability.

When proteins are consumed as a result of breakdown, they lose their antigenic properties, turning into amino acids. But some of the proteins can reach the distal parts of the intestine. And here the level of permeability of the small intestine plays an important role. If permeability is increased, then the risk of penetration of antigens into the internal environment of the body increases.

The permeability of the intestinal wall increases with prolonged fasting, with inflammatory processes and especially with a violation of the integrity of the mucous membrane.

With limited penetration of food antigens, the body forms a local immune response, producing antibodies. Secretory antibodies form non-absorbable immune complexes with most antigens, which are then broken down into amino acids.

The permeability of the small intestine may increase with expanded intercellular space. This leads to hypersensitivity to food proteins, which is often a trigger for diseases such as allergies.

Proteins found in cereals, soybeans, and tomatoes have the ability to penetrate the intestinal barrier. They are extremely poorly broken down and have a toxic effect on the intestinal epithelium.

Normally, the barrier of the small and large intestines is almost completely insurmountable for microorganisms. But with poor nutrition, hypothermia, intestinal ischemia, and damage to the mucous membrane, a significant number of bacteria can overcome the intestinal barrier and enter the lymph nodes, liver, and spleen.

With a nutritional deficiency of essential amino acids and vitamin A, the normal renewal of the mucous membrane is disrupted.

In addition to its direct functions, the small intestine influences neighboring organs, regulating their activity. Through functional connections, it coordinates the interaction of all parts of the digestive system.

Motor skills

Food masses move through the intestines due to rhythmic contractions of the latter. This process is called innervation. It is regulated by a network of nerve endings that penetrate the walls of the small intestine.

Digestion is a very delicate and precise process. Therefore, any sudden change in the chemical composition of food, and even more so the entry of harmful substances into the intestines, causes a change in the functioning of the secretion glands and peristalsis. The food mass is liquefied and motor skills are enhanced. Thus, this food is quickly eliminated from the body, which is one of the causes of intestinal disorders such as diarrhea (diarrhea).

Diseases

Based on the above information about the functions of the small intestine, it becomes obvious that any disruption in its functioning leads to disruption of the functioning of the entire body.

Diseases of the small intestine with severe malabsorption are quite rare. The most common are functional diseases in which intestinal motility is impaired. At the same time, the integrity of the mucous membrane lining the cavity of the small intestine is preserved. The most common disease, according to specialists from the Central Research Institute of Gastroenterology, is “ irritable bowel syndrome .” This disease occurs in 20-25% of the population.

In addition, malfunctions may result

- intestinal infections ,

- poisoning,

- worm infection,

- mechanical damage,

- congenital developmental anomalies.

Quite common is duodenitis , inflammation of the mucous membrane of the duodenum, duodenal ulcer .

Rare diseases - celiac , Whipple's disease , Crohn's disease , eosinophilic enteritis, food allergy , common variable hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphangiectasia, tuberculosis, amyloidosis, intussusception , malrotation, endocrine enteropathy, carcinoid, mesenteric ischemia, lymphoma.